Mary Lucile Stevens Seed Pearl Parure

Open FREE Unlimited Store Join Our Newsletter

Seed pearl jewelry were symbolic of purity and innocence and presented to a girl on her 18th birthday, as her first formal piece of jewelry

The Mary Lucile Stevens Seed Pearl Parure (pah-rur) is a full parure of seed pearl jewelry, once owned by Mary Lucile Stevens, who received it as a gift from her mother on the occasion of her 18th birthday in 1836. Seed pearl jewelry became popular in the last quarter of the 18th-century during the late Georgian period, and this popularity was maintained throughout the 19th-century, during the Victorian period, reaching its climax in the mid 1800s. In the United Kingdom, the Victorians developed a special liking for the appearance of the delicate almost lace-like seed pearl jewelry pieces. Symbolism and sentimentality were taken to an extreme during this period, with gemstone varieties, jewelry motifs and designs assigned special symbolic meanings. Pearls were believed to represent tears, amethyst devotion, diamond constancy, emerald hope, and ruby passion. The symbolic meanings attached to some of the motifs were, ivy for friendship, fidelity or marriage, daisy for innocence, bluebells for constancy, forget-me-nots for remembrance, mistletoe for a kiss, dogs for fidelity, butterfly for soul, doves for domesticity, lizards and salamanders for passionate love, snakes and serpents for eternity and commitment, etc. In the language of symbolism, seed pearl jewelry was also associated with purity and innocence. It was in this context that seed pearl jewelry during this period was often presented to a girl on her 18th birthday as her first formal piece of jewelry, or to a bride before her wedding.

The seed pearl parure given as an 18th birthday gift to Mary Lucile Stevens in 1836, was preserved as a family heirloom until 1984, when her male descendants donated it to the Smithsonian Institution

Thus, the Mary Lucile Stevens Seed Pearl Parure, in keeping with the traditions of the period, was given as a gift to Mary Lucile Stevens by her mother on her 18th birthday in 1836. Since then the pearl parure was preserved as a family heirloom and passed down succeeding generations of the family, always given as a gift to a daughter in the family on her 18th birthday, a mid 19th-century tradition preserved and strictly adhered to by the family. The pearl parure eventually came into the possession of a female member of the family in the mid 20th-century, who perhaps did not have a daughter to whom it could be bequeathed. The invaluable family heirloom was thus inherited by her sons, who in their wisdom decided, that the best place the priceless treasure would be preserved for posterity, would be the treasure house of the National Museum of Natural History, of the Smithsonian Institution. Accordingly, the descendants of Marie Lucile Stevens donated her seed pearl parure to the Smithsonian Institution in 1984, where it it is now put on display in the Museum's "Treasure House."

Characteristics of the Seed Pearl Parure

The Components of the Parure

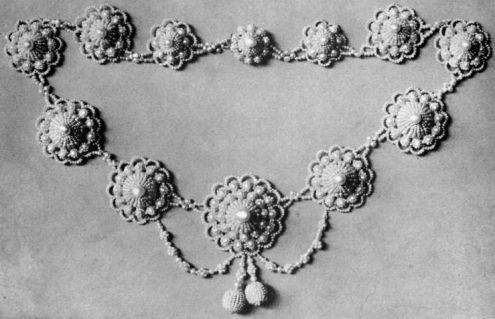

The Mary Lucile Stevens seed pearl parure, is a full parure consisting of a necklace, two bracelets, a pair of earrings, brooches and corsage ornament. The design of the jewelry is very delicate and ornate and consisted of foliage and flower motifs. The single blade, simple leaf motif, with a curved apex and the midrib, margin and veins, clearly depicted , is the repeated theme of this complete parure, incorporated in all the components, except the pair of earrings, based on a floral motif.

The Design and Features of the Pair of Bracelets

The centerpiece of each bracelet displayed at the top of the velvet lined leather case, is the leaf motif with the curved apex, midrib, margin and veins, clearly depicted by strands of seed pearls sewn into the design, carved out of thin sheets of mother of pearl, with white horse hair. Since the design is too delicate, with spaces between the veins, it is possible that the backing for the design was provided by some precious metal. Between the central leaf motif and the clasp on either side, is another leaf-like motif, smaller than the central motif. All three leaf-like motifs and the clasp on either side, are joined together by two strands of seed pearls and a metallic chain in the center, completing the design of the bracelet. The two bracelets are exactly identical to one another, and meant to be worn on each hand.

Mary Lucile Stevens Seed Pearl Parure

© Smithsonian

The Design and Features of the Necklace

The same leaf motif, with curved apex, midrib, margin and veins, is repeated on the necklace, whose centerpiece is occupied by the largest leaf motif in the entire parure, lined by seed pearls. On either side of the central large leaf motif are three smaller leaf motifs, all lined by seed pearls. A slightly different motif is depicted at one end of the necklace, occupied by the clasp, while the other end of the necklace is free on any motifs, having only the locking device of the clasp. The seven leaf motifs on the necklace, and the two ends of the necklace, are joined together by two long strands of seed pearls, and a central metallic chain, as in the case of the bracelets. The seed pearl necklace is the longest piece in the parure, and occupies the entire length of the lower side of the leather case and its two sides.

The Design and features of the Pair of Earrings, Pair of brooches and the Corsage Ornament

The central space of the display case, between the upper pair of bracelets and the lower necklace, is occupied by the pair of brooches, the pair of earrings and the corsage ornament. The corsage ornament occupies the center of this space, and a single earring and brooch are placed symmetrically on either side of it.

The Pair of Earrings

The earrings are pendant earrings, the pendant part being suspended from the ear stud by a hook and ring device. The motif of the pendant is a floral motif, with a central larger seed pearl surrounded by smaller seed pearls to form a rosette-like structure, which arises from the axil of two leaves or bracts, also studded with seed pearls. The ear stud also appears to be designed as a rosette or bunch of seed pearls.

The Pair of Brooches

The pair of brooches, placed on either end of the central space, are also designed as leaf motifs with the curved apex and margin, but without the midrib and veins. The space inside the margin of the leaf motif is completely filled with seed pearls. The identical pair of brooches were meant to be worn on the shoulders of the wearer.

The Corsage Ornament

The corsage ornament, usually worn on the chest of the wearer, is also made up of a single leaf motif, with the curved apex, margin, midrib and veins, with strands of seed pearls sewn onto the design. The size of this single leaf motif, is almost equivalent to the second largest leaf motif on the necklace, immediately after the largest leaf motif occupying the center of the necklace.

History of the usage of seed pearls in jewelry

What is a seed pearl ?

CIGJO Definition of a pearl

CIBJO, the French acronym for the International Jewelry Confederation, the body that sets the standards for the international gem and jewelry trade, defines a seed pearl as a small salt or freshwater natural pearl which is generally under 2 mm in diameter. This definition of seed pearl lays emphasis only on the size of the pearl in terms of its dimensions.

JVC Inc. Definition of a pearl

According to the Jewelers Vigilance Canada Inc. guidelines for the sale and marketing of diamonds, colored gemstones and pearls, revised in 2003, a seed pearl is defined as a nacreous cyst pearl that is under 2 mm in diameter. A cyst pearl is a pearl that has been formed within the living tissue of a mollusk, and was not in contact with the mollusk's shell. This definition too emphasizes the size of the pearl in terms of its dimensions, with the added qualification that it should be a nacreous cyst pearl, that excludes non-nacreous pearls and blister or mabe pearls.

Definition combining the size of the pearl both in terms of dimensions and weight

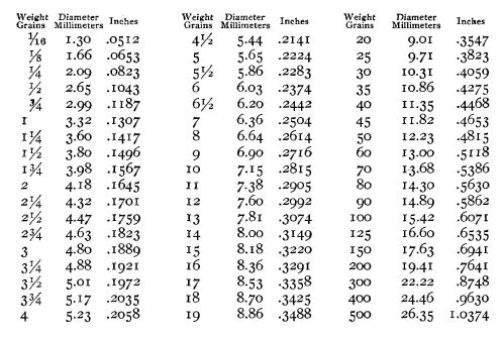

Chapter 13 of the Book of the Pearl written by Kunz and Stevenson and published in 1908, is titled "The Value & Commerce of Pearls." A table appearing in this chapter on page 328 relates the weight of round pearls in grains to their diameter in millimeters and inches, from a lower range of 1/16 of a grain to an upper range of 500 grains. This table can also be used to convert diameter in millimeters or inches to weight in grains. According to this table a diameter of 2.09 mm (approx. 2.00 mm) is equivalent to one- quarter (1/4) of a grain.

Table relating weight of pearls in grains to diameter in millimeters and inches from the Book of the Pearl, by Kunz & Stevenson

Thus, in the above definitions of seed pearls, the weight in grains equivalent to the diameter cut off point of 2 mm, below which the pearls are known as seed pearls, can also be incorporated. The seed pearl can thus be defined as a saltwater or freshwater, nacreous cyst pearl, whose size is less than 2 mm in diameter, and weight less than one-quarter of a grain (1/4 grain).

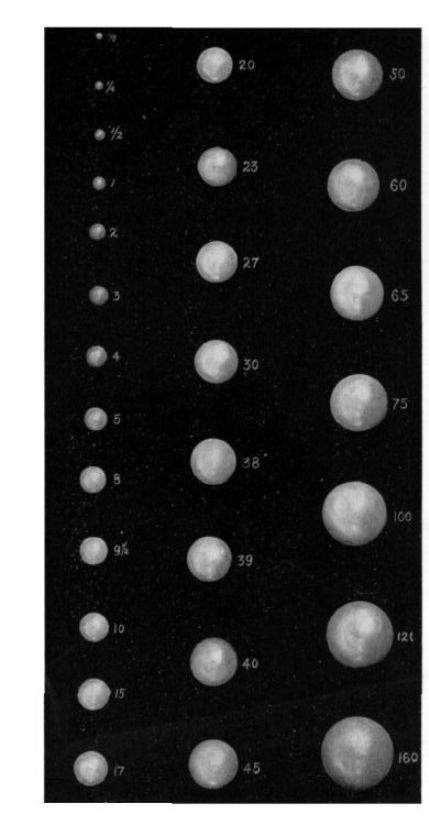

In the photograph below, extracted from Kunz & Stevenson's book, "The Book of the Pearl," published in 1908, the actual sizes of pearls ranging from 1/8 grain to 160 grains are clearly depicted. According to the definition of seed pearls, only the first two pearls at the top in the first vertical row, whose weights are 1/8 grain and 1/4 grain respectively, qualify to be labelled as seed pearls. The photograph clearly shows how the size of the pearls gradually increase as the weight of the pearl increases. This photograph is published for the benefit of the reader, as it gives a clear picture of what exactly a seed pearl is in comparison to pearls of other sizes.

Actual Sizes of Pearls from 1/8 Grain to 160 Grains

Extracted from the Chapter : Structure & Forms of Pearls in Kunz & Stevenson's book, The Book Of The Pearl, published in 1908

Sources of Seed Pearls

Ceylon (Sri Lanka), India, Persia and Arab countries of the Gulf were the main source of seed pearls in the world since ancient times

The greatest pearl producer since ancient times had been the pearl oyster species Pinctada radiata (previously known as Margaritifera vulgaris), whose natural home had been the Gulf of Mannar, the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea and had sustained the great pearl fisheries of Ceylon (Sri Lanka), India, Persia, and the Arab nations with a shore line on the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea. Most of the pearls produced by Pinctada radiata were seed pearls, although they also produced pearls of medium size, rarely exceeding 12-14 grains in weight, or 7.5-8.0 mm in diameter. Seed pearls were either formed singly or in clusters in the internal tissues of the oyster, such as the mantle or the gonads. Thus, the main source of seed pearls in the world in the past, had been Ceylon, India, Persia and the Arab nations of the Persian Gulf. According to Kunz, the quantity of seed pearls obtained in the Ceylon pearl fishery exceeds that of any other fishery in any part of the world.

Ceylon Pearl Oyster- Pinctada radiata

These pearls become the property of wealthy Chetties and Moormen (descendants of Arab settlers) from southern India, and Ceylon, as they had purchased the oysters that contained them at the auctions conducted by the British colonial authorities. The pearls are separated from the oysters by a process of putrefaction and washing. The separated pearls are either drilled by experienced pearl drillers in Ceylon, or taken to the pearl markets of India, such as in Bombay or Madras, cities under the administration of the British colonial authorities, or Hyderabad in the domain of the Nizam of Hyderabad, where they are sold to pearl dealers, who in turn sell them to the pearl jewelry manufacturers. The seed pearls are drilled and converted into beads, by experienced drillers in these cities, who then strung them into strands using horse hair or silk thread. Large quantities of seed pearl strands or un-stranded beads were exported to the jewelry producing centers of Europe and America in the 18th and 19th centuries. Seed pearls from the Persian Gulf too reached the pearl markets of India, such as Bombay and Hyderabad, where they were drilled and strung into strands, and either converted into jewelry or exported to the pearl markets of Europe.

Other sources of seed pearls in Asia were China and Japan

The species Pinctada radiata, or closely related species such as Pinctada fucata (Akoya pearl oyster) or Pinctada martensii (Akoya-gai pearl oyster), also occur in the waters off Japan, China, Korea, the Indonesian Archipelago and Australia, although they may not be the principal oyster species in these waters. In China and Japan significant quantities of seed pearls had been produced by this species of oyster, that was sufficient to sustain a seed- pearl drilling and stringing industry, that was exported to western countries to sustain a jewelry industry based on seed pearls in the late 18th and throughout the 19th centuries.

Venezuela in the New World became an alternative source of seed pearls in the 16th and 17th centuries, after Columbus discovered the pearl banks in 1498

In 1498, Columbus discovered the lucrative pearl banks of Venezuela off the Island of Cubagua, during his third voyage to the New World, a discovery that ironically led to his arrest and return to Spain in chains, as he failed to inform the King of Spain immediately of his new find. The exploitation of the Cubagua pearl banks, became the first lucrative venture of the Spanish in the New World, that brought greater returns than some other subsequent discoveries such as gold, silver and emeralds. The intensive exploitation of the pearl oyster resources of Venezuela for around one and half centuries, led to the complete depletion of resources, and the abandonment of the pearl banks around 1650.

The pearl oyster species of Cubagua pearl banks, were closely related to the Ceylon pearl oyster and the Persian Gulf pearl oyster, Pinctada radiata, and was given the scientific name Pinctada imbricata (Atlantic pearl oyster) Like the Ceylon pearl oyster, pearls produced by Pinctada imbricata were either seed pearls or pearls of medium size, ranging in weight from 2-5 carats (8-20 grains), with diameter of 6-9 mm. The shells like the Ceylon pearl oyster were thin and brittle and had no value as mother-of-pearl, in the shell button industry. Venezuelan seed pearls and medium sized pearls entered the European pearl markets via Seville in Spain. The seed pearls embroidered on to the dresses of European queens during this period, such Queen Elizabeth I (1533-1603), originated mostly in Venezuela.

Uses of seed pearls in history

Seed pearls had been put to several uses in Asia and Europe since ancient times. In all these uses the seed pearls had to be converted into beads by drilling, and invariably transformed into strands before usage.

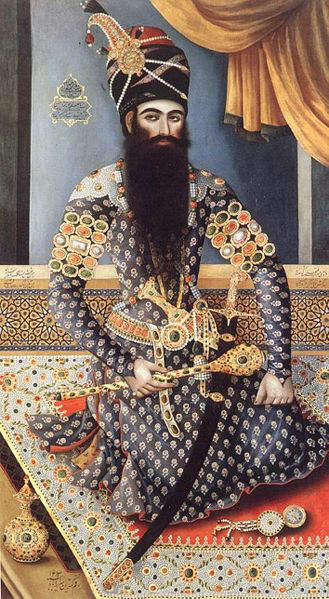

1) Seed Pearl Embroidery -

This was one of the first uses of seed pearls. In India seed pearls were used in large quantities for embroidery of the royal robes of Mughal Emperors and Empresses, Maharajahs and Maharanis of various kingdoms, and the Nizams of Hyderabad. The same practice was seen among the Qajar kings of Iran, such as Fath Ali Shah, who presided over a court of great brilliance. Fath Ali Shah's famous colored portrait, show him seated on a pearl and colored stone studded carpet, wearing a royal robe studded with seed pearls and other gemstones, on the collar and two zones on the upper arm. On this portrait, he is also seen wearing a "sarpech" on the turabn, lined with seed pearls, and four strands of seed pearls, radiating from the "sarpech," over his turban. In China too seed pearls were used in the embroidery of royal robes, such as during the period of the Manchu Qing dynasty, notable among whom was Empress Dowager Tz'u-Hsi (1861-1908), the most powerful ruler of the Qing Dynasty. In England, the use of seed pearl embroidery reached a climax during the period of Queen Elizabeth I (1533-1603), who is reported to have owned 3,000 pearl embroidered dresses. One of her famous portraits showing her wearing a pearl embroidered dress is the "Armada Portrait," in which pearls are seen studded all over the dress, and mainly on the elaborate collar surrounding her neck. She is also wearing a seven-strand pearl necklace, and 10 pairs of drop-shaped pearls are mounted on her elaborate hairdo, apart from the pair of drop-shaped earrings she is wearing. The portrait of Mary, Queen of Scots (1542-1587), also show her wearing a seed-pearl studded dress, apart from a large number of drop-shaped pearls, suspended from two arches, arising from her shoulders, and fixed just below her elaborate hairdo, and two other smaller arches surrounding her hairdo.

Armada Portrait of Queen Elizabeth the I

Mary, Queen of Scots

Fath Ali Shah- Safavid Emperor of Iran

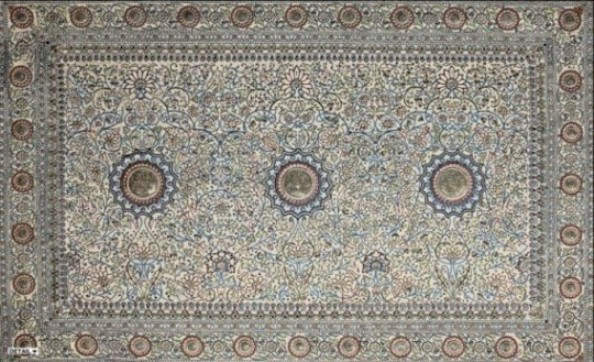

2) Seed pearl embroidered carpets

In India, the practice of embroidering seed pearls on to carpets, started during the Mughal period, and was prevalent until recent times, culminating in the creation of the most fabulous seed pearl carpet ever produced in the history of mankind, during the reign of the Maharajah Gaekwar of Baroda, Gaekwar Khande Rao (1856-1870), that came to be known as the "Pearl Carpet of Baroda." The carpet was in fact created by the Maharajah to fulfill a vow he had made to cover the tomb of the Holy Prophet of Islam, Prophet Muhammad, in the city of Medina, the hallowed sanctuary revered by Muslims all over the world. The rectangular shaped carpet, with dimensions of 2.64 meters by 1.73 meters, is made up of a combination of silk and deer hide, and densely embroidered with an estimated 1.5 to 2.0 million, natural seed pearls, known as Basra pearls, with an average diameter of 1-3 mm, and harvested from the pearl banks of the Persian Gulf, situated off the coastline of Bahrain and Qatar. The design of the carpet seem to have been inspired by design features of carpets from the Safavid period of Iran and the Mughal period of India. Apart from pearls, other gemstones incorporated in the carpet, are diamonds, rubies, emeralds and sapphires.

The Pearl Carpet of Baroda

©Sotheby's

Close up of one of the smaller peripheral rosettes of the Pearl Carpet of Baroda

©Sotheby's

In Iran, the tradition of embroidering carpets with pearls and other gemstones, dates back to the Sassanian period between the 3rd and 7th centuries A.D. One of the largest carpets ever made, the "Spring Carpet" with dimensions of 140 meters by 27 meters, depicting a garden in full bloom, covered the main audience hall of the Sassanian Imperial Palace at Ctesiphon, during the reign of Khusraw II, between 590 and 628 A.D. and was made of wool, silk, gold and silver, and embroidered elaborately with gemstones and pearls. During winter time, the king was said to have strolled along the length of this enormous carpet, savoring its many spring time scenes, such as flowers in full blossom, ripe fruits, birds in flight, and a broad green meadow border, designed in emeralds. Carpets decorated with pearls, rubies and turquoise, that adorned the palaces of Abbasid Caliphs in the 9th-century A.D. seem to have inspired the unknown author of the Arabian Nights fables, "Alf Lailah was Lailah" - A Thousand and One Nights, who writes of carpets studded with pearls and gemstones.

3) Use of seed pearls in jewelry

One of main items of jewelry produced in India, using seed pearl strands was the seed pearl necklace. Such necklaces were produced in two ways. One way was as Kunz describes in his book, The Book of the Pearl, as ropes produced by twisting together twenty or thirty strings of seed pearls. Apart from such rope necklaces used by the monarchy in India during that period, another type of necklace that was produced using seed pearl strands, was the "Panchlada," "Satlada," and multi-strand necklaces that combined together 5, 7 or many strands of seed pearls, without twisting. One fine example of such a necklace designed and produced in India, was the Umm Kulthum Multi-strand Pearl and Turquoise Necklace, made up of 10 strands of seed pearls interspersed with turquoise, whose centerpiece is an Art Nouveau style, peacock-shaped pendant, made of yellow gold and studded with pearls and turquoise. This necklace was designed in Bombay or Hyderabad in the 19th century. Hyderabad, the capital city of the Nizams of Hyderabad, had a thriving jewelry industry based on pearls, encouraged and patronized by the Nizams. Another famous seed pearl necklace, that once belonged to the Nizam's collection, but is now owned by the New York socialite and philanthropist Meera Gandhi, is the tri-colored seven-strand Ceylon Pearl Necklace.

The Ceylon Pearl Necklace made of seed pearls.

© ROM

Ummu Kulthum's Multi-strand Seed Pearl and Turquoise Necklace

The surge in popularity of seed pearl jewelry in Europe and America in the 18th and 19th centuries

The popularity of seed pearl jewelry reached a climax in Europe during the early Victorian period, from 1837 to 1860

Seed pearl jewelry first became popular in Europe in the last quarter of the 18th-century, and the first quarter of the 19th-century, during the Georgian period. The popularity of seed pearl jewelry reached a climax during the early Victorian period, also known as the Romantic period, that extended between 1837 to 1860, a period that signifies the happy moments in Queen Victoria's life, such as her youth, courtship, marriage and family life, until the death of her beloved husband, Prince Albert in 1861. During this period, burgeoning middle classes of Europe and the United States, were fascinated with pearl jewelry, and had the money to purchase them. They were fascinated by the look of the delicate and almost lace-like pieces of seed pearl jewelry, against the skin. Seed pearl jewelry were associated with purity and innocence, and was often presented to a girl on her 18th birthday, as her first formal piece of jewelry, or to a bride on her wedding day. A newspaper article that appeared in 1870, described seed pearl jewelry as, "exquisitely beautiful, constituting an appropriate and elegant present to a young bride."

Seed pearl jewelry first introduced to the United States by Henry Dubosq in the 1830s

Seed pearl jewelry were first introduced to the United States in the 1830s, by Henry Dubosq, who had seen this jewelry in Europe, and had studied the methods employed in designing them. He purchased a large quantity of English seed pearl jewelry, and brought them to the United States. He then hired a number of girls, and instructed them to dismantle the pieces carefully, to learn how they were made. He then asked the girls to re-string the pearls carefully with horse hair, and re-assemble them to form the original pieces. Employing these same girls he now started an industry to design seed pearl jewelry, importing his requirement of seed pearls from Europe initially, and later from the sources countries of India and China. The industry prospered turning out some fabulous pieces of seed pearl jewelry in the late 19th-century.

Seed Pearl Necklace Designed in the U.S in the 19th Century

A Chest filled with seed pearls from the Iranian Crown Jewels

Seed pearl jewelry were normally sold in sets or parures, contained in a jewelry box or case, consisting of a collar, a pair of bracelets, a pair of earrings, one or two brooches and a large spray or or corsage ornament. One or more larger pearls were sometimes incorporated in the design, as its centerpiece around which the seed pearls were arranged. Seed pearl jewelry were relatively cheap in the United States in the mid-19th century, seed pearl tiaras selling for between $75 to $300 each. In 1855, a $1,000 seed pearl set was one of the principal exhibits of Tiffany's at the International Exposition held at the Crystal Palace, New York, in 1855.

Kunz explains the vast difference in prices of a carat of tiny diamonds and a carat of tiny seed pearls

According to Kunz, seed pearls were sold by the ounce, a single ounce containing as many as 9,000 pearls. An ounce is equal to 150 carats. Thus, a single carat of pearls contain 60 pearls, which works out to 15 pearls per grain. The cost of an ounce of seed pearls around this period, in the early 20th-century was $48 to $60. Sometimes, pearls as small as 100 to a carat or 15,000 to the ounce, were drilled and used in designing seed pearl jewelry. Such pearls were only worth about 8-15 cents per carat or $12 to $22.50 per ounce. In the case of diamonds, rubies and sapphires, they can be cut as brilliants, even when they were as small as 250 to 300 pieces a carat or 300 x 150 = 45,000 pieces to the ounce. The cost of these diamonds were $200 to $300 per ounce, or $1.5 to $2.0 per carat. Thus a carat of tiny diamonds is worth approximately 10 times more than a carat of tiny seed pearls. The difference in the value of tiny diamonds and pearls is explained by Kunz, by the high cost of labor involved in cutting and polishing tiny diamonds. Pearls are naturally perfect gemstones and do not require cutting and polishing. They only need drilling and the cost involved is minimal.

All seed pearls used in the seed pearl jewelry manufacturing industry in Europe and the United States, were imported from China and India

All seed pearls used in the designing of seed pearl jewelry in Europe and United States were imported from China or India. Such pearls were already drilled and strung into strands or bunches. Chinese seed pearls were believed to be the finest and were already drilled and strung into bunches, each bunch weighing 3 ounces. The price of an ounce of Chinese seed pearls was $40 and the cost each bunch was $120. The Chinese seed pearls had been expertly drilled with a very fine aperture, that even a silk thread will not pass through the drill hole, and only horsehair could be used for stringing them.

The Indian seed pearls actually originated in Sri Lanka (Ceylon) and not in Madras

The Indian seed pearls were known as Madras pearls, Madras being the port of export, and not the place of production of the seed pearls. These pearls were actually Sri Lankan (Ceylon) seed pearls harvested from the pearl banks of the Gulf of Mannar. Some seed pearls were however harvested at Tuticorin, on the Indian side of the Gulf of Mannar, which was 330 miles (532 km) away from Madras. Their yield however was insignificant compared to the enormous yields of seed pearls harvested on the Sri Lankan side of the Gulf, which according to Kunz was the largest seed pearl fishery in the world. The Indian Madras pearls had a larger drill hole than the Chinese pearls, through which a silk thread could pass. The value of Madras seed pearls was $48 to $90 per ounce.

Horsehair obtained from a living horse was used in stringing pearls

Horsehair which was usually used in stringing pearls, was obtained from a living horse, and was known as pulled hair. Hair obtained from a dead horse was too brittle for work with seed pearls. Horsehair was sold in bunches of 8 to 14 inches in length, and was sold at an average price of $1.50 a pound (454 grams). Only the best and strongest hairs in a bunch were selected for seed pearl work, and it had been found that only about one ounce of horse hair was suitable for work out of an entire pound (16 ounces). In other words 15 ounces of horsehair from a pound were rejected.

Girls who were employed for seed pearl work were German or of German origin

The girls who were employed in seed pearl work were either German or of German origin, as they had already been exposed to such type of work at Idar-Oberstein, in the Duchy of Oldenburg, in Germany. The girls were paid $3.50 for an eight-hour working day. The work was difficult and needed clear daylight to see the tiny holes in the small pearls, and the mother-of-pearl shells, used a backing for the jewelry. Thus the restriction of the working period to 8 hours was more to do with the availability of light, than any other consideration. The time taken for stringing of pearls on an English scroll was about 12 hours, and needed an input of 1½ days of work.

All seed pearl jewelry were reinforced by a mother-of-pearl backing

All seed pearl jewelry were based on a mother-of-pearl backing or foundation. Mother-of-pearl obtained from Ceylon oysters or Venezuelan oysters were very brittle, and had no use either in the shell button industry or in the seed pearl industry, and were usually rejected. Heaps of broken pieces of such mother of pearl shells are still found today littering the coastline of the Kondaichy Bay in Sri Lanka, and the Island of Cubagua in Venezuela. However, mother-of-pearl produced in the Persian Gulf, known as Lingah shells, and other countries with pearl fisheries, such as Broome in Australia, China, Japan, Indonesia, Mexico, Panama etc. were quite strong and suitable for use in the shell button industry as well as the seed pearl jewelry industry. Thus, the mother-of-pearl shells used in the seed pearl jewelry industry, could have come from any country in the world with a pearl fishery, except Sri Lanka and Venezuela.

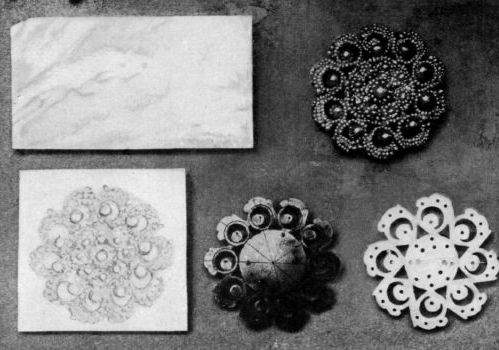

Steps in the production of a seed pearl brooch, from the Book of the Pearl

Horsehair used in seed pearl jewelry

Kunz gives a detailed description of how a seed pearl brooch is made

Kunz gives a detailed description of how a seed pearl brooch is made in his book, The "Book of the Pearl" under Chapter 14, titled "Treatment and Care of Pearls." Square-shaped mother-of-pearl shell plates with sides varying from 1½ inches to 2½ inches square were used for this purpose. The design is first drawn on a paper or cardboard of the same size as the mother-of-pearl plate, which is then cut out and pasted on the plate. Using this as a template, the design is sawn out on the mother-of-pearl plate, the empty spaces representing areas where no pearls are to be fixed. If a design is to be repeated regularly, a brass template is first cut out after drawing on paper or cardboard. Using this brass template as a guideline, the design is then cut out on the mother-of-pearl plate. The mother of pearl design is then pierced wherever a pearl is to be fixed. The pearls that would go into the design of the brooch are then carefully chosen, matching for size, color and other properties. Points that are symmetrical on the design, may require pearls of the same size. Each pearl is then secured on the mother-of-pearl outline with a strong horsehair thread. The final step in the completion of the brooch is the addition of a pin or catch on the reverse side of the brooch, that would secure it to the wearer's apparel. Kunz's account is accompanied by a photograph showing the design drawn on paper, the brass template, the mother-of-pearl outline pierced with holes, horsehair used in securing the pearl and the completed brooch.

You are welcome to discuss this post/related topics with Dr Shihaan and other experts from around the world in our FORUMS (forums.internetstones.com)

Related :

2) Umm Kulthum's Multi-strand Pearl & Turquoise Necklace

External Links :-

1) Seed Pearl Jewelry, 1836 - Treasure House, Legacies. https://www.smithsonianlegacies.si.edu/

2) Seed Pearl Jewelry - Jennifer Rodriguez. PBS

3) Georgian & Victorian Seed Pearl Jewelry - www.deniseyezbakmoore.blogspot.com

References :-

1) Seed Pearl Jewelry - www.vintagejewelrylane.com

2) Seed Pearl Jewelry, 1836 - Treasure House, Legacies. www.smithsonianlegacies.si.edu/gallery

3) Early Victorian Seed Pearl Jewelry - www.marigoldlane.com/antiques/victorian

4) Seed Pearl Jewelry - Jennifer Rodriguez. www.pbs.org

5) Georgian & Victorian Seed Pearl Jewelry - www.deniseyezbakmoore.blogspot.com

6) The Book of the Pearl - Kunz and Stevenson. Chapter 5 - Sources of Pearls, Chapter 6 - Pearl Fisheries of the Persian Gulf, Chapter 14 -Treatment and Care of Pearls

Powered by Ultra Secure

Amazon (USA) Cloud Network

Founder Internet Stones.COM

Register in our Forums

| Featured In

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|